|

|||||||

REVISTA TRIPLOV

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

EDITOR | TRIPLOV |

|||||||

| ISSN 2182-147X | |||||||

| Contacto: revista@triplov.com | |||||||

| Dir. Maria Estela Guedes | |||||||

| Página Principal | |||||||

| Índice de Autores | |||||||

| Série Anterior | |||||||

| SÍTIOS ALIADOS | |||||||

| Revista InComunidade (Porto) | |||||||

| Apenas Livros Editora | |||||||

| Arte - Livros Editora | |||||||

| Agulha - Revista de Cultura | |||||||

| Domador de Sonhos | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

[...]

We, writers

like to use pseudonyms. Stendhal's name was Marie-Henri Beyle; Mark

Twain's real name was Samuel Langhorne Clemens, Molière was the

criptonym of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin. George Eliot wasn't George nor

Eliot or even a man, she was a woman named Mary Ann Evans. Do you know

what Voltaire's name was? François-Marie Arouet. William Sydney Porter

hid himself under the false name of O. Henry. "(For reasons similar to

mine, but did not say that to the cop.)" That is a literary secret, ha,

ha![1]

The writer/narrator of Bufo & Spalanzani (1985), by

Brazilian writer Rubem Fonseca (n. 1925), answers this way to detective

Guedes when asked about the name with which he signs his books. Later,

the reader will become aware of the reason for the choice of Gustavo

Flavio: Ivan Canabrava, the character's real name, "ex-school teacher

hidden in a pseudonym, or, better, a refugee in a pseudonym" chose it

inspired by Gustave Flaubert, because at the moment of the adoption he

did not care about women, preferring, like Flaubert, "to channel all the

energy to literary creation"[2]. But today, he

admits, few years later and several books written, he endorses the

concept of "many lovers, many works" dear to Georges Simenon and Guy de

Maupassant. That is why he would choose Gustavo Simeon or Frederico

Guilherme (Frederick William), standing for Friedrich Nietzsche, marked

by the conflict "of construction and destruction, of life and death,

love and hate"[3].

Ivan disguises his own identity to protect himself from being

found out by the police, but he chooses a pseudonym which functions as a

strong marker of his inner self, of his thought and personal identity

and of his point of view on literary creation: like Gustave Flaubert, at

the moment when he had to choose a pseudonym, he thought that as a

writer he should follow the words: “reserve ton priapisme pour le style,

fous ton encrier, calme toi sur la viande... une once de sperme perdue

fatigue plus que trois litres de sang”[4]. However, if the

pseudonym had to be consistent and true to his beliefs concerning the

writing process and creation, nowadays he would have to choose another

one, one that would represent his current conception of poetics - a

combination between Georges Simenon’s and Guy de Maupassant’s ideas, or

the translation of Nietzche's first names. The translations into

Portuguese amuse the reader, because they sound ridiculous: however,

they only amuse the one who knows the secret behind the name, since he

is the one with the knowledge to relate the pseudonym to the name of the

inspiring author.

Pseudes (false) and onoma (name) is used by Ivan to

hide his true identity but at the same time to identify his personality.

As Rubens Limongi França wrote, a pseudonym is a name, different from

the birth name, “used by someone [...] at a certain course of action,

with the purpose of projecting a specific trait of his or her own

personality”[5]. Using a

pseudonym is not the same as anonymity, since it is a name with a

substance, not a nominis umbra (a name without a substance), as

Catherine A. Judd wrote in

“Male Pseudonyms and Female Authority in Victorian England”[6].

It simultaneously conveys and unveils something, because it entails

one’s renaming. This process can be compared to the choice of artistic

names: the writer chooses his/her second name or his/her mother's family

name, a part of his/her birth name, to present him/herself to the

public. On the basis of his/her choice, the reader can perceive the same

purpose of disentangling which is behind a pseudonym, even if the

veiling is less evident.

Despite the fact that, as the authors of

A Dictionary of

Anonymous and Pseudonymous Publications in the English Language

write,

the reasons “which lead writers to adopt a pseudonym or similar disguise

of identity are surely as various as human nature itself, and may well

defy classification”[7], the use of a

nom de plume is surely part of the creation of authorial identity, a

fictitious name not necessarily corresponding to an author’s fictional

life of. Soren Kierkegaard writes in his journals that when an author

desires to point out particular factors and dialectical details, he/she

uses poetic writers (pseudonyms), “poetized thinkers”[8], as he calls

them. This author may request anyone who wants to make any comment on

the matter to distinguish between his/her pseudonym and himself, but, of

course, by jumbling these together, “me and the pseudonyms, [...] he

believes that the pseudonym is one-sided and, thus, it is I myself who

said it.” That's why Kierkegaard writes an “Urgent Request by S.K.”

pleading to distinguish his pseudonymous work from the author’s, since

“It is the fruit of long reflection, the why and how of my use of

pseudonyms; I easily could write whole books about it.”[9] We may wonder if

his concern, and piece of thought, the reasoning why and how not to

betray the author’s position, thereby carrying a symbolic significance,

personifies and embodies some sort of ideology and its postulates.

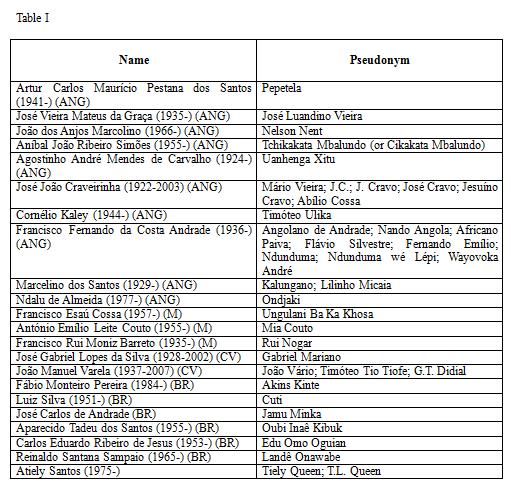

In the case of the Lusophone Literature, more specifically the

Literature of the Portuguese-speaking countries in Africa, that is from

Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau and São Tomé and Principe,

along with the Brazilian Literature, the analysis of the choice of

pseudonyms may clarify the historical shift experienced by the African

countries in the 20th century and beginning of the 21st

century as well as nowadays Brazil (Table 1), still involved in what can

be defines as a quest for the formula or formulae which define a unique

national identity formed by a multicultural and multiracial society.

Considering that a pseudonym is a means of communicating with the

reader, an indication of one's ideology and sense of identity belonging,

it is worth considering the predominant occurrence in African writers,

with Portuguese birth names and writing in Portuguese, of pseudonyms

created with the use of African languages, whether they are translations

of the original name (in the case of the Angolan writer Pepetela (1941),

which corresponds to his family name “Pestana” in Umbundu and means

“Eyelash”) or completely new names as Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa (1957), from

Mozambique, (pseudonym of Francisco Esaú Cossa, with its origins in a

Tsonga saying, which the author remembers from an infant ritual, meaning

“Finish with the Cossas, they are many.“) or

Tchikakata Mbalundu (i.e., Cikakata Mbalundu)

(1955), from Angola, whose name is Aníbal João Ribeiro Simões, who

chooses Umbundu to declare his belonging to one of the subgroups of the

ethnic group bantu, the Mbalundus ("Bailundos").

Agostinho André Mendes de Carvalho (1924), from Angola, whose

pseudonym is Uanhenga Xitu,

in Quimbundo, another Bantu language, wrote: “Agostinho Mendes de

Carvalho - Uanhenga Xitu… it's my name, it's not a pseudonym.

Everybody that saw me get born and grow

there is Calomboloca knows that I'm called UANHENGA. There are some

people that stubbornly say it's a nickname! My xará Kinguxi, the great

KINGUXI, gave me this name. One day I wrote an article to be published

and I signed.

Uanhenga Xitu… Rejected. I had to sign: Agostinho A. Mendes de

Carvalho.

It's

over, or the work is published under Uanhenga Xitu… or we'll wait for

the day when there will be someone who accepts the name by which I'm

known there in my sanzala, where I was born in 1924. The first literary

work that I wrote and came out to the public as I wished was in Cape

Verde - Chão Bom - Tarrafal[10]:

a line with the word “NO” engraved in the trunk of a red acacia.”[11]

Uanhenga Xitu, with his declaration,

gives voice to a generation of writers who lived the independence wars,

many of them descendants of Portuguese families and with Portuguese

family names, who used their literary names to vindicate an ideology and

a political position. The Angolan writer makes his creativity depend on

the use of his “true” name, the one given to him by Africa, a symbol and

a statement of the freedom that will come out after the independence.

Some of these authors wrote under their

“war names”, like Pepetela, who has kept his name up to now, or

Francisco Fernando da Costa Andrade (1936), whose war name was Ndunduma

wé Lépi. Some opted for a pseudonym which included a geographical

reference, such as the same Francisco Fernando da Costa Andrade

(Angolano de Andrade; Nando Angolano) or José Vieira Mateus da Graça

(1935) who signs José Luandino Vieira (Luanda, capital of Angola).

Pseudonyms create a clear division between colonial times and

post-colonial times, emphasizing the distinction between Portuguese

writers and African Portuguese-speaking writers, between Portugal and

their own countries, creating an imagined community linked by a sense of

belonging. In this case, the use of pseudonyms does not relate to

reasons of secrecy, on the contrary, they are public declarations of

their national identities, charged with a definitely meaningful role. As

Luisa Calé wrote, “pseudonimity, however, suspending the authors’

empirical identity does not mean withholding, let alone denying their

personal identity. On the contrary, pseudonimity supplements it with

another 'shorthand description', another form of reference. [...]

Pseudonyms project the geographical sense of neighbourhood onto an ideal

sense of community.”[12] In the

case of the writers mentioned so far, if there is a biographical

anchoring, there is also a national identity anchorage: the importance

of the space and time occupied by the authors is conferred by the use of

the African language.

The poet from Mozambique,

Marcelino dos Santos (1925) (also known as Kalungano and Lilinho Micaia

during the independence war) wrote: “The poets were the first great

revolutionary leaders in Africa. In the first place, we wrote poems with

words of liberation, such as “We need to plant” (from 1953, “We need to

plant/in the paths of freedom/ the new tree/ of the National

Independence”), then many of us took part in the armed war.”[13] The Portuguese

language was kept in the liberated colonies as a means of communication

among people (in Mozambique, for instance, there are more than forty

different languages) and of aesthetic expression. As the poet stated the

choice of the Portuguese code comprised a strategy of unity, a war

trophy, as the Angolan writer José Luandino Vieira puts it, since it not

only allowed for the expression of the ideas of freedom and independence

but also prevented the desegregation of the nations, each with a

plurality of languages otherwise likely to jeopardise a common

understanding among people and, thereby, their meaningful sharing of

common goals.

In 1972, Jorge de Sena, writing about the poetic work by Angolan

José Craveirinha (1922-2003) accounts for the difficulty of making

"African" poetry in African nations still under Portuguese ruling: "It's

easier to be African there, where the European culture, retiring with

those who embodied it only left behind a poison of Western bourgeois

nationalism which settled itself in power", "to look

africaníssimo/ real African,

where just a few write, using the European model, in French or English,

about their own for Africanness to the Europe of the universe."[14] But when it

comes to the Africanness of the countries "less European and more

'metropolitan'", it was expected that poetry would reveal the

polarization, the occurring division that resulted from this feeling of

double apartness.

When, in 1979, Luís Bernardo Honwana (1942) was asked in a

conference at the University of Minnesota about the choice of

maintaining the coloniser's language after the independence from

Portugal, he replied that the Portuguese language belonged to the people

of his own country, was also theirs, as well, in a natural way[15]. In fact,

the Portuguese language had been adapting itself for centuries to a

variety of human and geographical spaces in Africa, including its

various languages, and registers. It afforded new constellations in

literary tests, underpinned by neologisms, words from different local

languages and dialectal features, intertwined in standard European

Portuguese. The true liberation of these countries was the reinvention

of the coloniser's language as their own, entailing, however, not a

sterile hybridism, but a real creative and endless resourceful

endeavour, always capable of adaptation and renewal.

Distant and free from a commitment to

anti-colonial struggles, from the topics of blackness that characterises

certain African literatures in other languages or from the rhetorical

construction of the new nations, despite concerns about recent past

struggles and present hardships, literatures find in the language their

major way of affirmation, because the language conveys the future. The

Portuguese freed itself from is formality and became a re-invented

language, allowing writers to have an uninhibited relationship with the

language of creation.

What might seem paradoxical at a first glance, that is,

pseudonyms in both African and Portuguese languages as a tool for the

artistic expression, stands for a coherent stance not only with the

historical moment, the war of independence but also with the

contemporary linguistic innovation paradigm having featured the body of

literature stemming from African-speaking countries until modern times.

Some of the authors, after the independence, started writing with

their own names, but many kept their pseudonyms, even if the topics

having inspired many of the new generations of authors have given in to

the criticism of the liberation movements (at the core of long-lasting

and enduring civil wars) and of the political system likely not to be

fulfilling people's inner requests. Ondjaki (1977), the author of The

Whistler, born after the independence, chose a pseudonym in Umbundu,

meaning “the one who faces challenges”: it is no longer a statement of

independence or against the Portuguese coloniser, but a statement of

Africanness, i.e., a strong mark of belonging.

The consistency of African authors' multifaceted selection of

pseudonyms may help us reflect upon and establish some sort of relation

with a recent direction towards a new trend of Brazilian writers,

self-entitled as Afro-Brazilian authors or Black Literature authors, who

have adopted pseudonyms in African languages.

Fábio Monteiro Pereira (1985) inspired himself in the Yorubá

language to create Akins Kintê, “young warrior”; José Carlos de Andrade

is Jamu Minka; Aparecido

Tadeu dos Santos (1956) is Oubi Inaê Kibuk; Carlos Eduardo Ribeiro de

Jesus (1953) is Edu Omo Oguian.

Since

the 20s that African ascendency and Black affirmation in Brazil has been

defended by a group of intellectuals who saw in the image of the Black

Mother, a suffering and courageous mother, the slave having fed her own

children and the white lords' offsprings, the symbol of Brazil. Most of

them wrote for newspapers with pseudonyms hiding their true identities,

and used names like Raul, Helios or Ivan. These did not present any clue

to the author's empirical name. Helios, who was in fact Paulo Menotti

del Picchia (1892-1988), leading modernist poet, saw in the Black Mother

the tribute not to the black race, but to the African race, part of the

Brazilian people. José Correia Leite (1900-1989), who signed some of his

texts as Raul, in the periodical

Clarim, in 1930, defended that the Black Mother was the carnal

mother of all the mothers of the Brazilians[16], giving

emphasis to the idea of a multiracial nationality, “mestiça”. Brazil

would be a communion of races, whites and blacks mixed in a unique race.

However, more recently, the formation of

Quilombohoje, dedicated to the

Contemporaneous Afro Literature, which unites a group of Brazilian with

African ascendency (or better saying, Black, since African blood can be

found in a great part of the population),

demonstrates the will to defend Africanness and Blackness against a

society ruled by Whiteness and racial exclusion. Along with the

publication of the Black Journals (Cadernos

Negros) (in which Black writers can find their expression) this has

called the attention to a reality hidden in the White canon. As Jamu

Minka wrote in the poem “Efeitos Colaterais”: “In the misleading

propaganda/ the racial paradise/ hypocrisy hurts our future/ into a

bottomless pit”.

Before concluding, we wish to state that

the current analysis does not take into account whether AfroBrazilian

Literature or Black Literature is a valid concept in Brazil or if it is

in construction, as many critics believe, or even if it does not exist

at all, since it does not make sense to defend a Black Literature in a

country constituted of a melting pot of races and a plurality of

cultures: to accept Black Literature would mean to defend the existence

of an Arab Literature in Brazil, an Italian Literature there, among

others. The important issue is the statement that is made by these

writers and the link established by their choice of pseudonyms and the

will to find their lost roots in Africa, the roots which they believe to

be long denied to Black people in Brazil, though related to biased

assumptions on Black people's culture being inferior and subordinate,

vindicated, for instance, by Jamu Minka:

I found a flag

"Being

black" is a constant collocation in authors’ works issued in Black

Journals who with their use of pseudonyms give testimony to the process

of acceptance of their specificity as black and the awareness that

difference does not imply inferiority; it should rather be looked at

with pride. Literature in Brazil has to be open to “African attitudes”,

accepting its Black part, as Jamu Minka advocates:

Brazil and its

original sin: the dictatorship of whiteness and the vast repertoire of

disguises. For anyone who is visibly African, there was only this gift

of an exposed fracture. Our response: awareness and advocacy. We dare to

reinvent spaces of communication and we redefine ourselves in texts,

themes, readings, characters and stories of transformation.

[18]

Although there is a will to “re-join” Africa in a way to regain

one’s self identity, the knowledge of Brazil about Africa is

questionable, since in most of the cases poets and writers of the Black

attitude only have a partial or symbolical/mythological knowledge of the

African countries and culture, specially of the nowadays Africa. José

Eduardo Agualusa (1960-), an Angolan writer, once said that the African

countries and Brazil seem like two brothers, one very poor and the other

powerful and rich[19]. The very

poor knows everything about the rich brother and looks at him with

admiration and respect, but the rich brother knows nothing about the

poor brother. That is why it is also interesting to reflect upon the

choice of pseudonyms by authors such as

Atiely Santos (1975-),

who is known as a singer as Tiely Queen, one of the collaborators of

Cadernos Negros. Being a

writer of rap songs, she makes an option for a pseudonym that reminds

the reader of the names of American rappers, which can also show the

influence of the Black American culture in Brazil.

To conclude, this

analysis has to raise a challenging question: while the choice of

African languages based pseudonyms by the Lusophone writers and poets of

Africa is a strong marker of an historical shift and creates a distinct

division between colonial and post-colonial times or, nowadays,

emphasizes emphatically the national identity, does the same choice of

Afro-brazilian writers or Black Literature writers in Brazil have the

same meaning? These ones seem to be trying to recreate their own

identity through an idealized link to Mother Africa, since they are far

from bearing the knowledge of contemporary Africa (today, for example,

Portugal is acting as a real channel of culture awareness between the

two continents by a policy of promotion of the Lusophone various

cultures, arts and literatures; this along with African Lusophone

writers who have been divulging their own culture in Brazil). Apart from

their own clear or “hidden” objectives, they are testifying to a mixed

Afro-Brazilian culture which was created by the binomial of tradition

and innovation, having given Brazil one of its many faces. According to the anthropologist Darién J. Davis[20], Afro-brazilians are far from being an homogeneous group. Although, their artistic expression and their choice of pseudonyms, just like in the African Lusophone countries, serves as a statement concerning the awareness of problems of racism in Brazil, far from being a “melting pot” paradise. The pseudonym, the name with a substance that reveals more than hides, carries in the cases studied a strong sense of awareness and identity affirmation, stating the feeling of belonging to a chosen community and the will to stand for it. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

[1]

Bufo & Spalanzani,

Rio de Janeiro, Nova Fronteira,

(1985) 2011, p. 52. Translation by the author of this

essay.

[2]

Idem, p. 337.

[3]

Idem, p. 338.

[4]

Idem, p. 10.

[5]

Do

nome civil das pessoas naturais,

São Paulo,

Editora Revista dos Tribunais,

1975, p. 510.

Transl. by the author of this essay.

[6]

“Male Pseudonyms and Female

Authority in Victorian England” in

Literature in the marketplace: nineteenth-century British

publishing and reading practices, ed.

John O. Jordan, Robert L. Patten, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge

University Press, 1995, p. 250. (pp. 250-268)

[7]

A

Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous Publications in the

English Language,

(1475-1640), Vol. 1, Halkett and Laing, ed. J. Horden, Harlow

and London: Longman Group Limited, 1980.

[8]

Søren Kierkegaard’s

Journals and Papers:

Autobiographical, 1848-1855,

ed. Howard Vincent Hong, Edna Hatlestad Hong, Indiana University

Press,1978, p. 270.

[9]

Idem, p. 271.

[10]

Tarrafal was the place where the political prisoners

were sent to by the Portuguese fascism regime followers.

[11]

Author’s presentation page in Livros Cotovia Editor:

http://www.livroscotovia.pt/autores/detalhes.php?id=69

[12]

“Periodical Personae:

Pseudonyms, Authorship and the Imagined Community of Joseph

Priestley’s Theological Repository”

in 19 – Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth

Century, n.º 3, Literature and the Press: 1800/1900,

Birkbeck, University of London, 2006, p. 9.

http://www.19.bbk.ac.uk/index.php/19/article/viewFile/447/307

[13]

Apud “Escritores anseiam por difundir a cultura de

seus países e desfazer o estereótipo de um "continente exótico"”,

Luciana Lana, in Revista Literatura, Editora Escala, Rio de Janeiro, p. 1.

http://literatura.uol.com.br/literatura/figuras-linguagem/24/artigo145030-1.asp

[14]

Poesia e Cultura,

Porto, Edições Caixotim, 2005, pp. 166-167.

[15]

Apud

Luciana Lana,

op.cit., p.1.

[16]

“O dia da mãe preta” in O Clarim, 28 Setembro 1930, p. 1.

[17]

Cadernos Negros, 1, p. 35.

[18]

Cadernos Negros, p. 29.

[19]

Apud

Luciana Lana, op.cit.,

p. 1.

[20]

Afro-Brazilian: Time for Recognition, London, Minority Rights Group International Report,

2000. |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

© Maria Estela Guedes |

|||||||